Ten Rules for Depositions: Must-Know Evidence Rules for Effective Examinations

“If you don't know where you are going, you'll end up someplace else.” - Yogi Berra

When it comes to effective depositions, the examining attorney must master a handful of skills to ensure he or she is discovering new and necessary facts, exhausting (and pinning down) the witness' memory, and succinctly capturing key admissions. Our online Depositions Skills Clinic takes a close look at these issues and unpacks real-life examples of famous (and some infamous) depositions to illustrate what these skills look like in practice.

In addition to deposition tactics, a deposition admission is worthless unless it is an admissible admission. Too often, practitioners make the mistake of believing that the rules of evidence is something to consider if or when the case goes to trial. This is a mistake. A deposition transcript used to support a motion for summary judgment is useless if a key admission is buried in a meandering back-and-forth between the witness and examining attorney. And it's less than useless if the admission is inadmissible because the examining attorney failed to consider potential evidentiary hurdles. Mastering the rules of evidence is absolutely necessary for effective advocacy, and Evidence 101 is a great place to start. For now, here are ten must-know rules for effective depositions.

Rule 1: Witness Competency (i.e., Personal Knowledge)

California Evidence Code section 702 provides that with percipient witnesses, "the testimony of a witness concerning a particular matter is inadmissible unless he has personal knowledge of the matter." Before a witness can testify about a matter, there must be a foundation showing the witness' personal knowledge. The importance of personal knowledge is regularly underappreciated. Knowing something to be true is different from believing it to be true.

Take planet earth. Most witnesses will not hesitate to attest, if asked, that the earth is round. Everyone knows that. But if asked to identify what personal knowledge supports their knowledge, most witnesses come up short. They may have been told the earth was round in school (hearsay) or read about it in books (more hearsay). They have probably seen photos of earth taken from space. But without ever having been in space, those witnesses are incompetent to authenticate the pictures.

The earth example is admittedly silly (the roundness of earth is unlikely to be litigated anytime soon). But it does illustrate the susceptibility of witnesses and lawyers accepting or assuming personal knowledge when it may not exist. As the examining attorney, it is therefore useful to pin down both (1) what the witness knows, and (2) how the witness acquired such knowledge.

As the defending attorney, it is equally important to be on the lookout for testimony being offered without an adequate foundation. If a witness is unavailable at trial, there is a risk that incompetent testimony will be admitted because the trial court will conclude that objections related to foundation should have been made at deposition. California Code of Civil Procedure section 2025.460(b) provides as follows:

Errors and irregularities of any kind occurring at the oral examination that might be cured if promptly presented are waived unless a specific objection to them is timely made during the deposition. These errors and irregularities include, but are not limited to, those relating to ... the form of any question or answer....

Like California, the general rule in federal cases is that objections should only be to the form of the question. Fed. R. Civ. P. 32(d)(3). Practitioners are thus cautioned that "[i]f you intend to use deposition testimony at trial (and you usually do), phrase your questions to avoid all substantive objections—i.e., hearsay, no foundation, conclusions, etc. Otherwise, you may find you have conducted an expensive discovery procedure that does you little good in the long run." O’Connell & Stevenson, Fed. Practice Guide: Fed. Civil Procedure Before Trial (The Rutter Group 2017) ¶ 11:1558.

But there is an important exception to the general rule of form-only objections. As one treatise explains:

However—and this is an important "however"—even [other] objection[s] must be made at the deposition if the evidentiary defect presented by the question can be cured at the deposition. Too many lawyers believe that they need to object only as to the form of a question, and that all objections regarding the question's substance are preserved.... [A]s a defender you may need to object to the competency of a witness, to questions that seek inadmissible opinion or conclusion (for example, when a lay witness is asked for a legal conclusion), and to questions that lack foundation or are speculative....

Hecht, Henry L., Effective Depositions 354 (2nd ed. 2010) (emphasis in original).

Rule 2: Document Authentication

Authenticating documents is simple, usually taking just a matter of seconds, and yet attorneys routinely bungle the exercise. This can cause big problems at summary judgment or trial. In a past trial, the parties fiercely disputed the relevance of a document. Our trial team filed a motion in limine to exclude it, which the court denied in a lengthy order. But because the court ruled on relevance only, it did not decide admissibility. The court recognized that the threshold issue of foundation remained: "The court finds that the ... [m]emorandum that discusses [defendant's] response to the email may be admitted into evidence, assuming a proper foundation [is laid]...." (Italics added).

During trial, the plaintiff's lawyer failed to consider the importance of authenticating the document. He failed to do so during depositions and, when he tried to admit (and publish) the document during trial, he did so with a witness lacking personal knowledge of its creation.

The document was never admitted into evidence. But it could have. When considering authentication, California Evidence Code 1400 requires "(a) the introduction of evidence sufficient to sustain a finding that [the writing] is what the proponent of the evidence claims it is[,] or (b) the establishment of such facts by any other means provided by law." This means that the proponent must produce enough evidence to support a finding by a preponderance of the evidence. People v. Herrera, 83 Cal. App. 4th 46, 61 (2000). To be clear, the judge does not need to determine if the document is, in fact, authentic. He or she simply needs to decide if there is sufficient evidence that the jury could conclude the writing is authentic. As long as the proponent's evidence would support a finding of authenticity, the writing is admissible. The fact that conflicting inferences can be drawn regarding authenticity goes to the weight of evidence, not its admissibility. See e.g., McCallister v. George, 73 Cal. App. 3d 258, 262 (1977).

Like testimonial evidence, a document can be authenticated by anyone who saw the writing made or executed, including a subscribing witness. Cal. Evid. Code § 1413. Testimony from a percipient witness, speaking from personal knowledge as to the execution of a writing, is sufficient. People v. Estrada, 93 Cal. App. 3d 76, 100 (1979).

But first-hand knowledge is not the only way to authenticate a document. Evidence Code sections 1410 through 1421 list various methods of authentication of documents, and these methods are not exclusive. "California courts have never considered the list set forth in the Evidence Code sections 1410-1421 as precluding reliance upon other means of authentication." People v. Olguin, 31 Cal. App. 4th 1355, 1372 (1994). “Circumstantial evidence, content and location are all valid means of authentication.” People v. Gibson, 90 Cal. App. 4th 371, 383 (2001).

Rule 3: Business Records Exception

Trustworthiness is the rationale behind the business records exception (and many other hearsay exceptions). If a business relies on certain records in its day-to-day operations, they are likely trustworthy enough to be used in court. On the other hand, if a record was specifically created for a party's use in litigation, it is understandably less trustworthy.

For both the proponent and opponent of a business record's admission, the first step is understanding the foundational requirements of this hearsay exception:

1271. Evidence of a writing made as a record of an act, condition, or event is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule when offered to prove the act, condition, or event if:

(a) The writing was made in the regular course of a business;

(b) The writing was made at or near the time of the act, condition, or event;

(c) The custodian or other qualified witness testifies to its identity and the mode of its preparation; and

(d) The sources of information and method and time of preparation were such as to indicate its trustworthiness.

Cal. Evid. Code § 1271.

A common misstep is ignoring the opening language of Section 1271. The threshold requirement is that the writing record an "act, condition or event." A writing that purports to record only a conclusion does not qualify.

People v. Reyes, 12 Cal. 3d 486 (1974) illustrates this point:

[A] conclusion is neither an act, condition or event; it may or may not be based upon conditions, acts or events observed by the person drawing the conclusion; it may or may not be founded upon sound reason; the person who has formed the conclusion recorded may or may not be qualified to form it and testify to it. Whether the conclusion is based upon observation of an act, condition or event or upon sound reason or whether the person forming it is qualified to form it and testify to it can only be established by the examination of that party under oath....

Id., citing People v. Williams, 187 Cal. App. 2d 355, 365 (1960).

The next requirement is that the writing be made in the regular course of business. There are two important components to this requirement: (1) the business must routinely make a record of the act, condition or event in question as part of its regularly-conducted business, and (2) the record must have been made by someone with firsthand knowledge or be based upon information obtained from someone who had a business duty to observe and report the facts recorded as part of his employment. One way to think about this requirement is that the substance of the record must be reliable; it cannot simply be the regurgitation of inadmissible hearsay—even if it is made in the regular course of business. See e.g., Zanone v. City of Whittier, 162 Cal. App. 4th 174 (2008).

The timeliness of the record ("writing was made at or near the time of the act, condition, or event") is measured from the time of the act, condition or event to the time the document is entered or recorded. See Aguimatang v. California State Lottery, 234 Cal. App. 3d 769 (1991) (documents were admissible because the "data" was entered at or near the time of the event, even though the records were not "printed" until much later). This timeliness requirement is again tied to the idea that the record be trustworthy. Just as memories fade with time, a document prepared long after the act it is purporting to record is inherently untrustworthy. See e.g., Prato-Morrison v. Doe, 103 Cal. App. 4th, 229 (2002).

The requirement that a witness attest to both the record's identity and mode of preparation can cause unanticipated challenges for lawyers or witnesses unfamiliar with the details of Section 1271. The witness must be able to testify to the document's "identity and the mode of its preparation[.]" Too often, witnesses will provide unchallenged and conclusory testimony that the document was made and kept "in the regular course of business." An attorney anticipating his or her opposition to the admissibility of the writing must not wait until trial to challenge it. A thorough cross-examination to test the custodian's actual knowledge (or lack thereof) of the document's mode of preparation can lay an effective foundation for the document's exclusion.

Rule 4: Refreshed Recollection

"What documents did you review to prepare for your deposition?" It is among the most commonly asked questions at the outset of depositions. And yet, whether the answer is permissible or privileged turns on a thorough understanding of the attorney work-product doctrine and the evidentiary rules about documents used to refresh a witness' memory.

Kerns Construction Co. v. Superior Court, 266 Cal. App. 2d 405 (1968) examined the interplay between Evidence Code sections 771 (refreshed memory) and the attorney work-product doctrine. California Evidence Code section 771, subdivision (a) provides that, "if a witness, either while testifying or prior thereto, uses a writing to refresh his memory with respect to any matter about which he testifies, such writing must be produced at the hearing at the request of an adverse party and, unless the writing is so produced, the testimony of the witness concerning such matter shall be stricken."

The plaintiff in Kerns allegedly suffered an injury from a gas explosion. Kerns Construction Company (Kerns) was sued along with other co-defendants, and Kerns deposed a witness who worked for the gas company when the explosion occurred. Id. at 408. The witness testified to having prepared investigation and accident reports. Id. The witness further acknowledged that he had "no memory ... independent of the reports." Id. However, when the deposing attorney requested the reports' production, the gas company refused on the ground it would violate the attorney-client privilege and work-product doctrine. Id. at 408-09.

The Kerns Court agreed the reports were protectable under the attorney-client privilege and work-product doctrine. But when the witness relied on them to provide deposition testimony, it presented a "conflict between a liberal interpretation required under our own rules of discovery and the liberal construction in favor of the exercise of the attorney-client privilege." Id. at 412. The Court decided that any privileges were waived once the witness relied on them to provide testimony:

The witness had his reports, which he had previously prepared, in his possession at the time he testified and, additionally, made reference to them in order to answer questions propounded to him on the cross-examination. Having no independent memory from which he could answer the questions; having had the papers and documents produced by Gas Co.'s attorney for the benefit and use of the witness; having used them to give the testimony he did give, it would be unconscionable to prevent the adverse party from seeing and obtaining copies of them. We conclude there was a waiver of any privilege which may have existed.

Id. at 410 (italics added).

With respect to the work-product privilege, the Court explained "the privilege rested with the attorney and was waived by the attorney when he produced the reports to the witness upon which to premise his testimony. The attorney cannot reveal his work product, allow a witness to testify therefrom and then claim work product privilege to prevent the opposing party from viewing the document from which he testified." Id. at 411.

Rule 5: Past Recollection Recorded

California Evidence Code section 1237 provides that "[e]vidence of a statement previously made by a witness is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if [1] the statement would have been admissible if made by him while testifying, [2] the statement concerns a matter as to which the witness has insufficient present recollection to enable him to testify fully and accurately, and [3] the statement is contained in a writing which:

(1) Was made at a time when the fact recorded in the writing actually occurred or was fresh in the witness' memory;

(2) Was made (i) by the witness himself or under his direction or (ii) by some other person for the purpose of recording the witness' statement at the time it was made;

(3) Is offered after the witness testifies that the statement he made was a true statement of such fact; and

(4) Is offered after the writing is authenticated as an accurate record of the statement.

(b) The writing may be read into evidence, but the writing itself may not be received in evidence unless offered by an adverse party.

In practice, lawyers (and witnesses) often conflate the concepts of a witness' refreshed recollection with a witness' past recollection recorded. If a document simply refreshed the witness' memory, the content of the writing should not be read aloud (let alone admitted). Instead, the witness should simply affirm that his or her memory is refreshed and then testify to what he or she remembers. If the memory is not refreshed but the document constitutes a past recollection recorded, the attorney should (1) ask the requisite questions to meet the requirements of Section 1237, and (2) have the witness read the writing into the record.

Rule 6: The Attorney-Client Privilege

The attorney-client privilege is absolute. Unlike other exclusions that can sometimes be outweighed by countervailing policies, evidence protected by the attorney-client privilege may not be ordered regardless of relevance, necessity, or circumstances. Costco Wholesale Corp. v. Superior Court, 47 Cal. 4th 725, 732 (2009). And while the attorney-client privilege is sacrosanct, there can be a tendency for lawyers defending depositions to expand its application beyond its permissible scope. Lawyers may instruct clients to not answer questions about what steps were taken to look for a lawyer. Any questions about the where, when, or length of attorney-client meetings are often—and improperly—deemed off-limits by overzealous counsel.

When taking a deposition, it is essential to know what is and is not protected by the attorney-client privilege. California Evidence Code section 954 provides that "the client ... has a privilege to refuse to disclose, and to prevent another from disclosing, a confidential communication between a client and lawyer...." See also United States v. Martin, 278 F. 3d 988, 999 - 1000 (9th Cir. 2002).

With respect to timing, the privilege attaches upon the initial client consultation and continues so long as the "holder" (i.e., the client) is in existence. David Welch Co. v. Erskine & Tully, 203 Cal. App. 3d 884, 891 (1988). Accordingly, and also because such conduct and communications do not fit within Section 954, questions about what a party did to look for his or her lawyer are absolutely fair game in a deposition.

Another allowable are of inquiry are questions that ask for independent facts related to a privileged communication. While the substance of "confidential communications" are protected, "[t]he privilege does not protect 'independent facts related to a communication; that a communication took place, and the time, date and participants in the communication.'” 2,022 Ranch LLC v. Superior Court, 113 Cal. App. 4th 1377, 1388 (2003), citing State Farm Fire & Cas. Co. v. Superior Court, 54 Cal. App. 4th 625, 640 (1997).

Rule 7: The Attorney Work Product Doctrine

"What documents did you review to prepare for your deposition?" This question is asked at virtually every deposition, and it is—in many instances—objectionable. California Civil Procedure Code section 2018.010 codifies the attorney "work product" doctrine and specifies the conditions under which disclosure of an attorney's work product may be compelled. McKesson HBOC, Inc. v. Superior Court, 115 Cal. App. 4th 1229, 1238 - 1239 (2004). The doctrine is designed to preserve a lawyer's right to prepare his or her case for trial without his or her adversary gaining access to the work. So if a witness' attorney handpicks the documents to review before a deposition, does identifying such documents implicate the attorney work product doctrine?

But what if reviewing the documents refreshed the witness' memory. As discussed earlier, Section 771 provides that writings that refresh a witness' memory must be produced at the request of the adverse party. A prior article closely examined the interplay between the attorney work product doctrine and Section 771. Bottom line: To avoid objections (or, if defending, to avoid waiving work product protections), the question should be: "Did you review any documents that refreshed your memory prior to today's deposition?"

Rule 8: Hearsay

Hearsay is an exclusionary rule with so many exceptions that simply memorizing the rules and their exceptions (and the elements of each exception) is—while necessary—not sufficient to apply the rule effectively during the quick pace of depositions or trial.

Because hearsay objections are reserved for trial, practitioners can make the mistake of failing to thoughtfully consider hearsay during depositions. And yet depositions are often the place where parties can lay the proper groundwork to establish the applicability (or non-applicability) of an exception to the hearsay rule. Such testimony can be vitally important both during trial as well as when the court considers various hearsay challenges in in limine motions. Beyond memory, litigators must have a system to quickly and accurately identify objectionable hearsay. Consider, for example, the following:

Q Did you talk to anybody on Friday?

A Yes. I spoke with John on the phone.

Q What did John say?

A He said, “I’m sick.”

Before considering whether the above testimony might or might not be considered hearsay, knowing the rationale to exclude hearsay is helpful. We know that the “[t]he very nature of a trial is [the] search for truth.” Nix v. Whiteside, 374 U.S. 157, 158 (1986). To get to the truth, lawyers have just one weapon: questions. “Cross-examination is the greatest legal engine ever invented for the discovery of truth.” Lilly v. Virginia, 527 U.S. 116, 123 (1999). With these issues in mind, let's consider the above example, not through a formal hearsay analysis, but rather through a lens emphasizing the importance of cross-examination.

Suppose the case turned on whether John did or did not feel sick. How could the jury ascertain the truth? The jury would undoubtedly wish to hear from John. Had he called a doctor? Did he take any medication? To determine whether John was indeed sick, cross-examination would be essential.

But suppose the case did not turn on whether John was sick, but it instead turned on whether the testifying witness was told John was sick. Suppose the testifying witness was a caretaker who was required (but failed) to drive to John’s house the moment he or she learned that John felt sick. Rather than John’s sickness (at the time of the call) being an issue, the issue is whether the caretaker was told that John felt sick. In this case, there would be no need to cross-examine John.

Practitioners are often told that to recognize hearsay, they must analyze whether the out of court statement is offered for the truth. If the value of the evidence turns on the credibility of someone who cannot be cross-examined, it is invariably a statement that is being offered for the truth of the matter asserted. Once hearsay is recognized, the rule is simple: Hearsay is not admissible. Fed. R. Evid. 802; Cal. Evid. Code § 1200(b). And if that is the case, it is important to quickly identify potential hearsay exceptions.

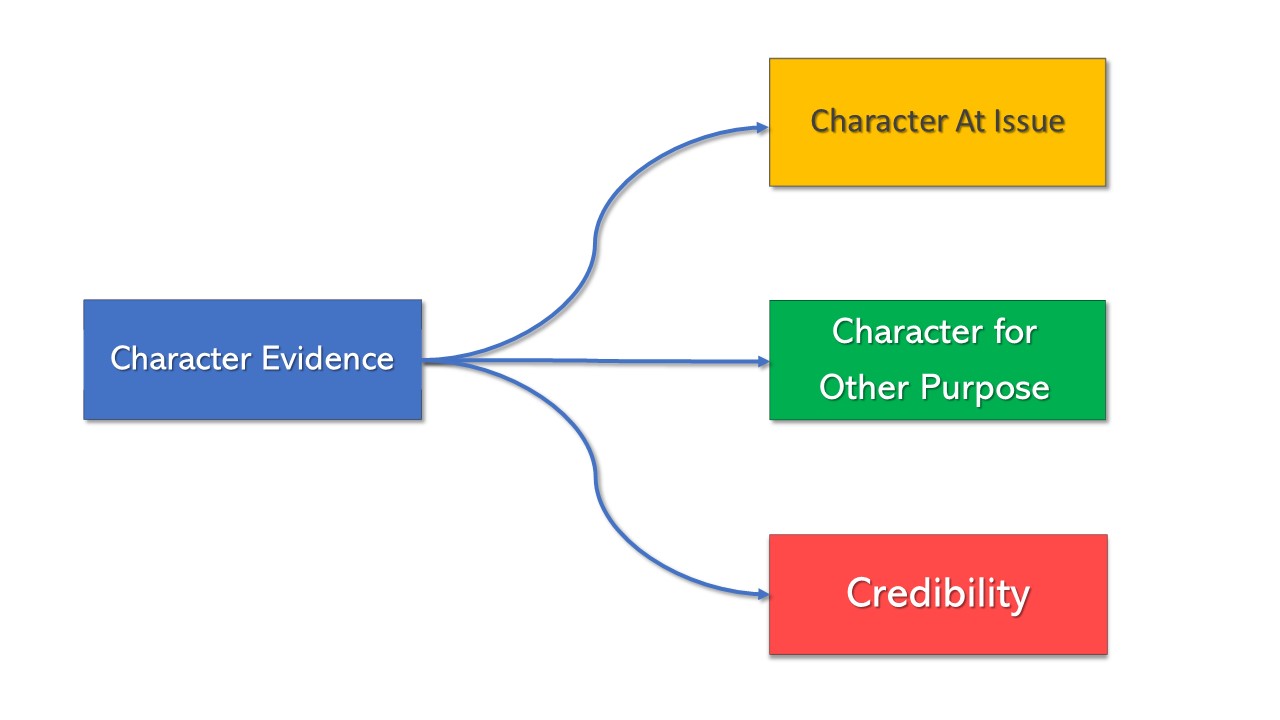

Rule 9: Character Evidence

Character evidence is similar to hearsay in that there is a general rule of inadmissibility followed by so many exceptions that they often gobble up the general rule. But what can make character evidence trickier is that even when it is admissible, there are specific rules about the type of evidence that is allowed.

"Although the term 'character' is not defined in the Evidence Code, it is generally described as 'the aggregate of a person's traits' and means 'disposition' (i.e., the tendency to act in a certain manner under given circumstances)." People v. Shoemaker, 135 Cal. App. 3d 442, 446-47 n.2 (1982), citing Model Code of Evidence, rule 304, com. (1942).

Before examining the occasions when character evidence is admissible, we must first distinguish character evidence from "habit or custom" evidence. While character evidence is evidence of a person's propensity or tendency to act in a certain way, "[c]ustom or habit involves a consistent, semi-automatic response to a repeated situation." Bowen v. Ryan, 163 Cal. App. 4th 916, 926 (2008). Unlike character evidence, "[a]ny otherwise admissible evidence of habit or custom is admissible to prove conduct on a specified occasion in conformity with the habit or custom." Cal. Evid. Code § 1105. Whether something is character evidence or habit evidence is a preliminary fact the trial judge decides. And the line between character and habit evidence can be difficult to discern.

Once dealing with character evidence, one of the exceptions to the general rule of inadmissibility is when a person's character or a trait of his character is at issue. Cal. Evid. Code § 1100. A person's character (or character trait) is typically an "ultimate fact in dispute" whenever that person's character is an issue under the substantive law or the pleadings in the case. See Pugh v. See's Candies, Inc., 203 Cal. App. 3d 743, 757 (1988). See's Candies involved an action for wrongful discharge brought by a managerial employee. Id. at 748. During trial, there was testimony from See's employees, former employees, and business associates that the plaintiff was disrespectful to his superiors and subordinates, disloyal to the company, and uncooperative with other administrative staff. Id. at 756. The Court of Appeal affirmed the admission of such character evidence because the plaintiff's "character or personality in the workplace was in issue under the substantive law and in the pleadings of the case." Id. at 757.

Once there is a determination that character or a character trait is relevant, Section 1100 provides that such character evidence can be in the "form of an opinion, evidence of reputation, and evidence of specific instances of such person's conduct."

Even if character evidence is not directly at issue in the case, subdivision (b) of Section 1101 provides a laundry list of instances in which character evidence can be admitted to prove something other than a person's propensity or disposition. Subdivision (b) provides as follows:

Nothing in this section prohibits the admission of evidence that a person committed a crime, civil wrong, or other act when relevant to prove some fact (such as motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, plan, knowledge, identity, absence of mistake or accident....

Cal. Evid. Code § 1101(b) (italics added).

The final category in which character evidence can be admissible is when it goes to the witness' credibility. Evidence Code sections 780, subdivision (e), provides that, with respect to character evidence that can be used to attack or support a witness' credibility, it is limited to the witness' "character for honesty or veracity or their opposites." Section 786 clarifies this limitation even further, providing that, "[e]vidence of traits of his character other than honesty or veracity, or their opposites, is inadmissible to attack or support the credibility of a witness."

Character evidence can be difficult. For a more in-depth analysis, check out The Admissibility of Character Evidence: Demystifying the Rules and their Application.

Rule 10: Settlement Discussions

Attorneys often assume that any communication that encompasses a settlement offer, demand, or negotiation is automatically off-limits and privileged for all purposes. But a close reading of Section 1152 suggests the rule may be more limited:

Evidence that a person has, in compromise or from humanitarian motives, furnished or offered or promised to furnish money or any other thing, act, or service to another who has sustained or will sustain or claims that he or she has sustained or will sustain loss or damage, as well as any conduct or statements made in negotiation thereof, is inadmissible to prove his or her liability for the loss or damage or any part of it.

Cal. Evid. Code § 1152(a).

Meanwhile, California Code of Civil Procedure section 2017.010 provides the allowable scope of discovery:

Unless otherwise limited by order of the court in accordance with this title, any party may obtain discovery regarding any matter, not privileged, that is relevant to the subject matter involved in the pending action or to the determination of any motion made in that action, if the matter either is itself admissible in evidence or appears reasonably calculated to lead to the discovery of admissible evidence.

The plain language of Sections 1152 makes no mention of settlement discussions being "privileged." "The statutory protection afforded to offers of settlement does not elevate them to the status of privileged material." Covell v. Superior Court, 159 Cal. App. 3d 39, 42 (1984). The inquiry must therefore turn on "whether settlement negotiations is 'relevant to the subject matter involved in the pending action,' or 'appears reasonably calculated to lead to the discovery of admissible evidence.'" Id. A more in-depth discussion on this issue can be found here.

Conclusion

Depositions are the building blocks for successful litigation. But those blocks crumble if the testimony is objectionable. Mastering these ten rules can help ensure the admissibility of all facts gathered and admissions collected at your next deposition.

David Sugden is a shareholder at Call & Jensen in Newport Beach, California.

Join our community!

Register for our complimentary resources of blog articles, course and event updates to receive a 20% off coupon.