People v. Mooring: Remembering Step-Three From Sanchez's Step One

With it being almost three years since People v. Sanchez, 63 Cal. 4th 665 (2016), most lawyers are at least familiar with its holding. Indeed, prior articles on this blog have summarized the case and explained how to question expert witnesses post-Sanchez. But with familiarity, certain details can be overlooked. Take Michael Jordan. The most casual fan has an instant memory of his storybook career with the Bulls, the multiple championships, even his brief retirement to give baseball a go. But playing for the Washington Wizards? For two seasons? These are details we knew at some point, but then immediately forgot. Forever.

With Sanchez, there can be a tendency to oversimplify its application. Sanchez states that "[w]hen any expert relates to the jury case-specific out-of-court statements, and treats the content of those statements as true and accurate to support the expert's opinion, the statements are hearsay." Id. at 686. Once such hearsay is recognized, there can be a temptation to assume the statement is not allowed and start asking those hypothetical questions that Sanchez revitalized.

People v. Mooring: Remember the Hearsay Exceptions

But hearsay is just hearsay. Before concluding that the identification of hearsay constitutes a dead end with respect to case-specific statements an expert relied on, consider exceptions to the hearsay rule. People v. Mooring, 15 Cal. App. 4th 928 (2017), is a good illustration of this.

Mooring reads like a jayvee version of Breaking Bad. The case begins in 2011 when law enforcement officers searched the home of Lanita Denise Davis and Darrell James Mooring and found over 4,000 pills. Id. at 932. Most of the pills were found in prescription bottles that bore the names of Davis and Mooring, though some identified their son, Darrell Mooring Jr. Id. In addition to the drugs—a laundry list that included morphine, methadone, oxycodone—police also found several empty pill bottles and a police scanner. Id. at 933.

The police seized the drugs, which did not please the soon-to-be-indicted Mooring. Mooring drove to the police station and "asked for 'his pills ... that [had been] taken' from the residence." Id. at 933. In a summary dripping with understatement, the Court explained that "[w]hen the police officer refused to return the pills, [Mooring] became angry." Id.

Perhaps to complement his police station visit, the first defense presented at trial was nothing if not gutsy: no crime was committed because the pills were all properly prescribed to Mooring and Davis. Id. at 936. To support this theory, defense counsel called Dr. Edward Manougian, who prescribed "up to 800 pills a month, comprised of Vicodin, OxyContin ... and Valium." Id. According to the record, "Dr. Manougian believed defendants were using the prescribed pills, not selling them." Id. The jury may have been less than enamored with Dr. Manougian's testimony because the record further reflected that:

[C]ertain pharmacies stopped filling Dr. Manougian's prescriptions. In 2012, Dr. Manougian's medical license was revoked in part because he had "not engaged in any formal course of study" regarding "treatment of pain or pain management" and had no "special training or experience in addiction."

Id. at 935.

The second defense was more nuanced. It can be best summarized as the never-judge-a-pill-by-its-looks defense. Towards this end, the defendants sought to exclude the testimony of a criminalist who testified as an "expert in presumptive identification of prescription pills." Id. at 933 - 934. This expert witness, Shana Meldrum, had ten years of experience as a criminalist, and had spent more than four hundred hours training in analyzing and identifying suspected controlled substances. Id. at 934. Ms. Meldrum utilized a subscription-based website known as Ident-A-Drug to presumptively identify certain pills. Meldrum explained the process during trial:

I type the markings on the pill into the website and it gives me either one match or a list of possible matches that the pill may be. And based on the color and the shape and the imprints on the pill, I make a determination as to whether or not to report that out as as presumptive identification.

Id. at 934.

This method was generally accepted in the scientific community, and Ms. Meldrum had presumptively identified prescription pills using Ident-A-Drug more than two thousand times. Id. The defendants argued that Ms. Meldrum's testimony regarding the Ident-A-Drug website was hearsay, and that its admission violated the rule excluding case-specific hearsay as stated in People v. Sanchez, 63 Cal. 4th 665 (2016).

Remembering Sanchez's Step One's ... Three Steps

To consider the defendants' argument, the Mooring Court revisited Sanchez. Prior to the Sanchez opinion, trial courts often allowed expert witnesses to relay case-specific hearsay to the jury. This allowance was justified on two grounds:

First, Evidence Code section 802 "allows an expert to 'state on direct examination the reasons for his opinion and the matter ... upon which it is based,' [accordingly] an expert witness whose opinion is based on such inadmissible matter can, when testifying, describe the material that forms the basis of the opinion." Accordingly, so long as the hearsay was of a type reasonably relied upon by experts, the expert could describe the material that formed the basis of his or her opinion. See e.g., People v. Bell, 40 Cal. 4th 582, 608 (2007).

Second, to prevent the potential harm of allowing the expert to relay incompetent hearsay, trial courts could provide a limiting instruction that "matters admitted through an expert go only to the basis of his opinion and should not be considered for their truth." Id.

Sanchez rejected this approach. The Court reasoned that when an expert relies on case-specific hearsay to form an opinion, the validity of the opinion ultimately turns on the truth of such hearsay. See Sanchez, 63 Cal. 4th at 682-83. And if the opinion turns on the truth of the hearsay, it is illogical to tell the jury the hearsay should only be considered for the expert's "basis," but not its "truth"—because for the opinion to have an adequate "basis," the facts need to be "true." Id. at 684.

The Sanchez Court adopted the following rule: "When any expert relates to the jury case-specific out-of-court statements, and treats the content of those statements as true and accurate to support the expert's opinion, the statements are hearsay. It cannot be logically maintained that the statements are not being admitted for their truth." Id. at 686. As a result, Sanchez restored the distinction between general background hearsay (which can be relayed to a jury) and case-specific hearsay (which cannot).

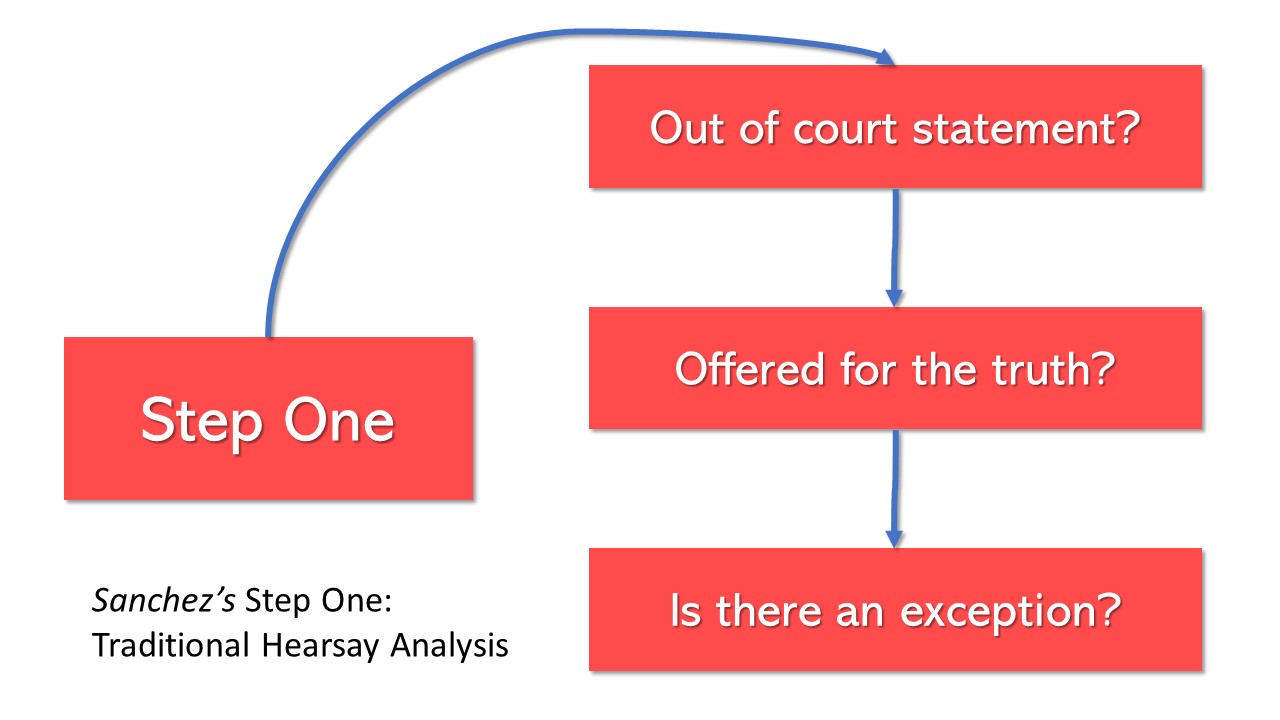

In implementing this rule, the Sanchez Court discussed the required "two-step analysis" when addressing the admissibility of out-of-court statements. In civil cases, only the "first step" applies:

[A court' must engage in a two-step analysis. The first step is a traditional hearsay inquiry: Is the statement one made out of court; is it offered to prove the truth of the facts it asserts; and does it fall under a hearsay exception? If a hearsay statement is being offered by the prosecution in a criminal case ... a second analytical step is required.

Id. (emphasis added).

Mooring's Application of Sanchez: A Traditional Hearsay Analysis

In response to the defendants' contention that the Ident-A-Drug website was hearsay offered to prove its truth, the Attorney General argued that it fell within "published compilation" exception found in Evidence Code section 1340. Mooring, 15 Cal. App. 5th at 937.

The published compilation exception requires: "(1) the proffered statement must be contained in a 'compilation'; (2) the compilation must be 'published'; (3) the compilation must be 'generally used ... in the course of a business'; (4) it must be 'generally ... relied upon as accurate in the course of such business; and (5) the statement must be one of fact rather than opinion." Id., citing People v. Franzen, 210 Cal. App. 4th 1193, 1206 (2012).

Mooring went through each of these elements to conclude that the Section 1340 exception applied. The Ident-A-Drug website was, for example, relied upon as accurate by the crime lab in conducting its business. Id. at 938. Indeed, Ident-A-Drug had a commercial incentive to be accurate and reliable. Id. It was a subscription based website, and its success was premised on being trustworthy. Id.

Conclusion

Mooring is a helpful reminder to not oversimplify People v. Sanchez. Sanchez does not impose a per se exclusion of case-specific hearsay with expert witnesses. The Court explained: "What an expert cannot do is relate as true case-specific facts asserted in hearsay statements, unless they are independently proven by competent evidence or are covered by a hearsay exception." Sanchez, 63 Cal. 4th at 686 (emphasis in original).

David Sugden is a shareholder at Call & Jensen. He can be reached at [email protected].

Join our community!

Register for our complimentary resources of blog articles, course and event updates to receive a 20% off coupon.